Sideshow Outlaw: Elmer McCurdy

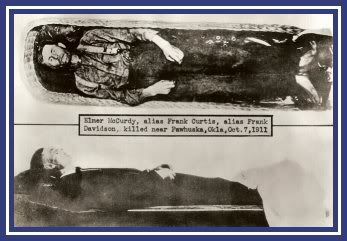

Elmer McCurdy, alias Frank Davidson, in his casket.

He was killed near Pawhuska in 1911.

Picture courtesy of Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries.

In December 1997 a BBC film crew came to Oklahoma. They were looking for anyone who knew anything about a little-known outlaw, Elmer McCurdy. My curiosity was aroused as to their investigation of Elmer McCurdy. Why not some of the infamous Oklahoma outlaws such as Bill Doolin, the Dalton brothers, and other well-known figures? I was determined to meet the crew and satiate my curiosity. But, as we've often heard, "The best laid plans of mice and men go oft astray." So it was with my desire to meet the film crew. Other events interfered and I never was able to meet them.

The answer to their quest may lie in the fact that Elmer McCurdy died in 1911, but his body was lost for sixty-six years and didn't reach the grave until 1977. How could this happen? That is "the rest of the story."

Elmer was born in Washington, Maine in January 1880 to Sadie McCurdy. Sadie was seventeen at the time, was living at home, and was unmarried. Elmer's father was never identified. Suspicions at that time pointed to Charles Davis, a cousin, who was seven years older than Sadie and had lived with the McCurdy's for a short time.

In order to protect Sadie and the family from the embarrassment of an out of wedlock child, Sadie's brother George and his wife Helen, who had no children of their own, apparently adopted Elmer. One year later, they had a child of their own, whom they named Charles. Both Elmer and Charles were very fond of George and Helen McCurdy, and both of the boys came to know Sadie as "Aunt Sadie."

In February 1890, George contracted tuberculosis and died. After George's death, Sadie moved into the house with Helen in order to help care for the boys. With George gone, Helen decided that she could no longer care for Elmer. She then asked Sadie to assume responsibility of Elmer, and Sadie agreed.

Together, they explained the circumstances of his birth to Elmer, who seemed at first to accept the disclosure with no adverse reaction. However, the full realization of the dilemma occurred to him quickly: His "mother" was his "aunt," and his "aunt" was actually his "mother." At the age of fifteen, he began to feel that somehow his mother had betrayed him. At that time, he began to drink heavily and became rebellious. In January 1895, he ran away from home.

He lived with his grandparents, Harden and Abbey McCurdy, for three months. Influenced by his grandfather, Elmer settled down with his job as an apprentice plumber. He learned the trade quickly and well. However, after three months on the job, he decided to move back home with Sadie, his mother. He not only accepted her well but also became quite loving and protective of her. In 1899, Sadie became ill, and her parents cared for her in their home. Sadie died in August 1900 at the age of thirty-eight. On September 28, little more than a month later, Sadie's father died of Bright's disease.

After three deaths, Elmer was on his own and left Maine to seek his fortune elsewhere. He arrived in Lola, Kansas in 1903. Working as a plumber, he moved from town to town, living in Cherryville, Kansas and Webb City, Missouri. In 1907, however, Elmer tried something new-he moved to Cherryville, Kansas and tried his hand as a miner.

MILITARY SERVICE

That same year, 1907, Teddy Roosevelt called for one hundred thousand troops for the ongoing occupation of the Philippines and Cuba. Elmer saw this as an opportunity to see the world. He enlisted and was assigned to the 13th infantry. Again, however, his "best laid plans" went astray. By the time Elmer had finished his processing, the 13th infantry had returned to Fort Leavenworth from the Philippines.

At Fort Leavenworth, he was assigned to the quartermaster's department, even though his profession was as a plumber. After the three-year expiration date of his enlistment was over, he was officially discharged from the Army on November 7,1910.

After his discharge he located in St. Joseph, Missouri, looking for work. Apparently he had no luck and began drinking heavily. On November 20, 1910, Elmer, along with another man, Walter Shapilrock, was arrested for having burglar tools in their possession. Under the Criminal Statutes of Missouri at that time, "Possession of burglars' tools" was a felony punishable by imprisonment in the penitentiary for not less than two years or more than ten years.

On December 16th the two men waived formal arraignment and entered a plea of "Not guilty." As they waited for their trial date in the Buchanan County jail, Elmer met Walter Jarrett. Jarrett had been arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct and disturbing the peace. He had been tried in open court, found guilty of the charges and sentenced to a $50 fine or 50 days in jail. Since Jarrett did not have $50, he was put in jail. He had already served 30 days of his sentence when he met Elmer. Walter bragged of his adventures in Oklahoma, where he claimed he had robbed several banks. Elmer's interest was aroused by these stories, and he and Walter became "friends." Upon his release, Walter offered Elmer an invitation to visit him at any time.

The day after Walter Jarrett's release from jail, Elmer McCurdy went to trial. He was successful in convincing a jury that the tools in his possession at the time of his arrest were not "burglar" tools. Instead, he said, the tools were necessary for his profession as a plumber. He was released from jail, and within a month he was in Lenapah, Oklahoma, with his new friend, Walter Jarrett.

Walter introduced his friend, Elmer McCurdy, as "Missouri McCurdy, an expert cracksman from St. Joe." Elmer perceived that these words were meant to impress Walter's brothers, Lee and Glen, so he could convince them to participate in a robbery. Walter's plan was to rob the Iron Mountain train.

TRAIN ROBBERY

On the night of March 23, 1911, Walter Jarrett; Lee Jarrett; Elmer McCurdy; and Ab Connor jumped aboard the train near Lenapah. This was Elmer's first attempt at cracking a safe, and he misjudged the amount of nitroglycerin to use: the safe became too hot. According to reports by the Pacific Express Company, the explosion threw the door of the safe across the car and tore a gaping hole in the entire side of the express car. Twisted silver coins lay on the floor of the express car. $4000 in silver, which had been inside the safe, was melted and blown into one corner of the car. Elmer retrieved a coal pick and attempted to chop the melted silver from the wall. Apparently he failed, for when the train arrived in Kansas City, a crowbar was used to extract the melted silver from the wall. The "take" in the robbery was a mere $450.

After this fiasco, Walter and Elmer decided to split their partnership. Walter went back to Missouri, while Elmer headed for the Osage Hills, using the alias "Frank Curtis." He applied for and got a job with the Selby-Downard Construction Company in Pawhuska. After two weeks on his new job, he met a man named Amos Hayes. Amos confided to Elmer that he intended to rob a bank in Chautauqua, Kansas. His motive was partly revenge after the bank had refused him a loan, despite the fact that "the bank had plenty of money," He offered Elmer a cut of the money if he would participate in the robbery.

McCurdy agreed, and on the night of September 21, 1911, Amos Hayes, Elmer McCurdy, and a third man named "Higgins" broke through the wall of the bank where they could directly enter the vault. Once inside, Elmer set a nitroglycerine charge, running a long fuse into the alley through the hole in the wall. The explosion was gigantic.

According to the Sedan Times Star, "It blew the outer door off the safe and threw it with terrific force against the front door of the vault. That vault door, with its iron frame, was blown out of place and across the room to the plate glass window. It plowed its way through the furniture, leaving everything in it path a complete wreck."

Elmer and Amos hurried back into the vault, but they found the inner door of the safe still intact. Elmer set another charge of nitroglycerin on the inner door, but before he could fire it, Higgins called out that lights were going on all over the town. Amos and Elmer scooped up some silver and gold coins that were in a counter tray on the top of the safe, jumped on their horses and rode hard out of town. The total take: $150.

After that robbery, Amos told Elmer about the Osage Indian payments that were transported via the Katy railroad. They made plans to rob the train of its bounty. On October 4, 1911, Amos, Elmer, and another man named Sears held up the M.K. & T. passenger train Number 23. The location of this robbery was about three miles south of Okesa, Oklahoma, at 1:00 a.m. However, the befuddled outlaws found that they had held up train Number 29, which ran between Kansas City and Oklahoma City and did not carry a great amount of money. They escaped with little booty after rifling the mail and baggage car.

The Bartlesville Enterprise on October 6, 1911 stated:

"The haul made by the robbers was one of the smallest in the history of train robbing. They failed to find as much as a copper cent in the safe in the express car. The express agent opened the door for them and allowed them to look in. They took $40 in currency and a Hampton watch worth $25 from the mail clerk, a cravnette coat worth $25 from the conductor McCormick, and from the train auditor, Paul Hagan, they took an automatic revolver. They also made away with two gallons of whiskey, and during the holdup; they knocked in the head of two kegs of beer and drank part of the contents. After the robbery, the men escaped hastily."

Soon over fifty officers, including several federal officers who had been rushed down from Pawhuska, were on the robbers' trail. Elmer, using the alias "Frank Amos" was trailed to a ranch belonging to Charley Revard. After drinking with the ranch employees, he asked for a place to sleep and was shown to the haymow. He had been asleep only a few minutes when posse members Dick Wallace and the brothers Robert and Stringer Fentons arrived. They took stations about the barn and waited for daylight.

GUN BATTLE

As the morning sun began to rise, Elmer fired the first shots. The first three were aimed at Stringer. Then he turned his attention to Dick Wallace. Elmer exchanged shots with the posse for an hour. When the gunfire suddenly ceased, a young man from the ranch slipped carefully inside and found Elmer McCurdy dead.

That evening, the cortege escorted Elmer's body into Pawhuska in the back of a wagon. The procession stopped in front of Johnson Funeral Home, and Elmer's body was removed from the back of the wagon, where he was placed in a wicker basket and photographed by William J. Boag. Shortly thereafter, law officers arrived and identified the dead man as Elmer McCurdy. Elmer's body was then turned over to the undertaker.

The undertaker, perhaps suspecting that he might be forced to hold the body longer than usual, removed the bullet from Elmer, tied off the ruptured arteries, then added arsenic to the usual embalming fluids, a practice, according to paleontology studies, was commonly found in the preservation of Egyptian mummies.

Everyone assumed that Elmer's body would soon be claimed, but after six months' residence in the back room of the mortuary, the curious onlookers found that his preservation was still perfect. They also discovered that when his body was removed from the slab, Elmer could still stand upright. As "The Embalmed Bandit," he had already become an object of local interest. Mr. Johnson, the mortician, decided to dress Elmer in the clothing he had worn in his last gunfight and stand him in the comer of the mortuary. To add a touch of realism, someone placed a rifle in Elmer's hand, and there he stood for five years.

In October 1916, two men went to see the Sheriff and county attorney concerning the display of Elmer's body. One of them stated that he was a brother and said his mother, who lived in Kansas, was worried and sick.

The county attorney informed Mr. Johnson to turn Elmer's body over to them. These men were James and Charles Patterson. James was an owner and manager of Patterson Carnival Shows, and Charles, his brother, was a traveling salesman for the Lesh Oil Company. James's carnival show had stopped in Arkansas City, Kansas, where his brother Charles lived. Charles told James about Elmer McCurdy in Pawhuska and a plan was made for the retrieving of the body.

On October 5, 1916, Mr. Johnson received a long distance telephone call from these men in Arkansas City. On October 7th, Elmer was shipped out on the Midland Valley Railway. The next morning, The Great Patterson Shows left Arkansas City for Woodward, Oklahoma, playing there for a week and then went into the Texas panhandle. A short time later, word came back to Pawhuska that Elmer was being exhibited in a street carnival show in West Texas. Elmer was in show business now.

Elmer was on the road with James Patterson until 1922, when he was sold to Louis Sonney. Sonney had a wax figure museum sideshow called, "The Museum of Crime." In the sideshow he had a collection of outlaws in wax such as Jesse James, Bill Doolin and the Dalton brothers. He made wax figures of any outlaw who became infamous. Elmer became an extra attraction, a real, dead outlaw.

Sonney's wife, Dorothy, recalled Elmer's appearance by noting that "He had shriveled up so much and he was so tiny. He looked like an eight year old child." Elmer stayed with this show until 1971, when Sonney sold his sideshow to Spoony Singh, owner of the Hollywood Wax Museum. When his sideshow didn't work out, Elmer was sold in October 1971 to Ed Liersch.

Liersch and a partner, D.R. Crydale, leased space on the Long Beach Pike in California and set up a wax figure exhibit of their own. At this time Elmer's casket had long since fallen apart, and he was now in a cardboard box. At their show Elmer was displayed as, "The 1,000 Year Old Man." Five years later, Elmer was reduced to hanging in a funhouse in Long Beach called, "The Laff in the Dark." It was on December 7, 1978, and the "Laff in the Dark" was closed to the public. It had been leased to Universal Television Studios for the filming of the "Six Million Dollar Man."

The episode called for a secret missile control room camouflaged as a carnival attraction. A prop man began to take down what looked like the figure of a shriveled old man; he was hanging by the neck from a rope in the ceiling. He had been painted several times with phosphorus paint, making him glow in the dark. The prop man grabbed the figure under its right arm and reached up to loosen the noose around its neck. As he jerked at the noose, he felt something hit his foot. He looked down and saw the lower half of the figure's right arm. Long Beach Police were notified.

The following is a portion of the Police Report #765-0028, filed December 8, 1976: Filing officer and Criminalist E. Williams went to the Nu-Pike in company with the Fire Department Personnel. The Laff in the Dark (sic) located at 21O-A-A-A West Pike A venue was entered, and their attention was drawn to the human-like display, which was hanging from a rope. Criminalist E. Williams and filing officer examined the display, (sic) and noted beneath the outer covering there appeared to be bone-type structure having bonelike joints. There was also noted to be a small trace of hair on the back leg. The display remarkably resembled a human cadaver in size and proportion.

Elmer was transported to the medical examiner's office for the county of Los Angeles, where he was tagged as John Doe #255, and Dr. Joseph Choi performed an autopsy. Dr. Choi confirmed that the remains were human and that the cause of death was from a bullet wound. He further found that the body had been embalmed for burial by the use of arsenic, Which had mummified his body. Arsenic had only been in use for embalming between 1905 - 1930. Dr. Choi then determined that since arsenic had been used in the embalming process, the John Doe must have died in a time period after 1905 and before the late 1920's or 1930's.

On December 9th Donald Drynan, a spokesman for the coroner's office, issued a news release of the information to date. The Sonney family then contacted the Los Angeles Police Department and confirmed that the body was that of Elmer McCurdy.

The Los Angeles medical examiner's office promptly contacted the Oklahoma State Historical Society; the Historical Society then contacted Dr. John Ezell, curator of the Western History Collection at the University of Oklahoma in Norman, Oklahoma. The curator at the Western History Collection found a picture of Elmer McCurdy that carried the inscription:

Elmer McCurdy. Shot by Sheriff's posse near Pawhuska. Okla. 10/7/ 1911.

Learning about the picture and date, the Oklahoma Historical Society dug deep into its archived newspaper files and found an archived newspaper, the Oklahoma City Oklahoman edition published on October 8, 1911. There, on the front page, sixty-five years old, was the story of Elmer McCurdy and his spectacular last stand.

Again, the cycle completed itself, and no relatives claimed Elmer's body. Finally, a unit that called itself, "The Indian Territory Posse of Oklahoma Westerners," stepped forth. First, Dr. Clyde C. Snow, osteologist from Oklahoma City was sent to Los Angeles to establish identity of the mummy. He began the difficult task primarily through comparison of the photographs which had been taken of Elmer shortly after his death with the X-rays of the remains. On April 14th, the Los Angeles Times announced: "Tests Conclusive, Scientists Agree. Mummy Is Indeed Oklahoma Badman."

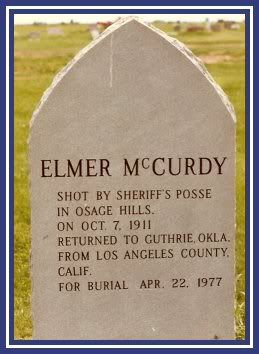

On Saturday, April 16, 1977 Elmer left Los Angeles for Oklahoma's Territorial Capitol, Guthrie. The Gill-Lessert Funeral Home in Ponca City brought down an appropriate hearse-horse drawn, glass sided, draped inside with rich velvet curtains. Truman Moody provided a coffin he had made out of white pine. The lid was embossed with a plain wooden cross. The Warren Monument Company of Guthrie furnished a gray granite tombstone with the inscription:

Even though Elmer wasn't a famous outlaw from Oklahoma, his site for burial was chosen in Guthrie's Summit View Cemetery Boot Hill section, where many of the more famous desperados rested. His final resting-place is beside one occupied by one of Oklahoma's most famous outlaws, Bill Doolin.

The morning of the burial, a funeral home in Oklahoma City brought Elmer to the Smith Funeral Home in Guthrie. At 10:00 a.m., the burial procession assembled on Pine Street, about a quarter of a mile north of the cemetery entrance. The funeral home brought Elmer's coffin out in an automobile and transferred it there to the black, horse-drawn hearse. The cortege then proceeded to Elmer's last resting-place. No automobiles were used: the only transportation was buggies and horseback.

The horse-drawn hearse edged close by the grave, and the pallbearers dismounted. They deftly carried Elmer's coffin, adorned with a spray of white lilies to the gravesite. Someone spoke words on his behalf, and he was lowered into the grave. After the coffin rested in the bottom of the grave, a ninth grade girl from a local History Club walked up and dropped a single red rose.

At that time, a Dolese cement truck poured two and one-half yards of concrete on the top of the coffin. Elmer had finally reached his permanent home, and the concrete was used to make sure he stayed there. Elmer McCurdy still rests in Boot Hill. Visiting his grave is similar to taking a trip back in history. It took him sixty-six years to find his home.

Elmer, Rest in Peace.

Sources:

The Arkansas City Daily Traveler, October 7, 1916.

The Bartlesville Evening Enterprise, October 9, 1911.

The Bartlesville Morning Examiner, October 5, 1911.

Lbid. October 6, 1911.

Lbid. October 9, 1911.

Basgall, Richard J., The Career of Elmer McCurdy. Deceased.

The Coffeyville Daily Journal. March 24,1911.

Lbid. March 25,1911.

Joyce, Christopher and Eric Stover, Witnesses from the Grave.

Kelly, Billy, "The Triumphal Return of Elmer McCurdy," Real West, July 1997.

The Oklahoma City Sunday Oklahoman, October 6, 1911.

The Oklahoma City Times, October 4, 1911.

The Pawhuska Capital, October 12, 1916.

The Sedan Times-Star, September 22,1911.

Additional information from Chris Haynes.

My name is Chris Haynes. I am a Teamster (truck driver) in the motion picture industry. On December 7th I was working with the Set Dressing Crew of "The Six Million Dollar Man" I am the person who discovered Elmer was a person and not "Paper Mache" as other members of the crew working in the "Laff In The Dark" attraction thought. I noticed Elmer had been cut open and crudely stitched back together (Autopsied). I noticed human features that would not be present on a prop or dummy. I was pointing these things out to another crew member. As our discussion went on I said if you move his hands away from his private areas you will see something that is not "Paper Mache". I moved his hand a bit to expose his private parts and his arm snapped off at the elbow. Inside I could see dried muscle and bone. This definitely was not a dummy.

At this time I went outside of the building and notified the Long Beach, CA Police Officer, who was assigned to our production that day, that there was a human cadaver in the fun house. He came in and saw Elmer hanging there. He could see this man was mummified and had been dead for a very long time. He said. "Ha! Just what Long Beach needs, another dead sailor." and he left. I then notified the Long Beach Fire Department's Fire Safety Officer on the set. He too thought it was funny and said. "Hey! I'm gonna call out the paramedics and tell them I have a guy suffering from extreme dehydration." It was at this time I had to leave the set to return to the studio and pick up a load for another location. Somehow someone else from the Fire Department did come to the set and saw Elmer. He notified the Long Beach Police who in turn contacted the Los Angeles County Coroners office to see if this was indeed a human or a made up prop. The rest is history.

I would like to clear up a few errors in the part of Elmer's story involving me. I am not a Prop Man or Technician. I was not trying to remove the noose from Elmer's neck or take him down. I was not surprised by his arm falling on my foot as it didn't. Elmer was not taken down from where he was hanging until the Los Angeles County Coroner's office removed him.

The funeral parlor that embalmed Elmer did not remove the bullet from his body as it was still there when he was re-autopsied by Los Angeles County Coroner Dr. Joseph Choi. It was a 32-20 bullet and was lodged in his hipbone.

|