Tragedies and Hardships of the

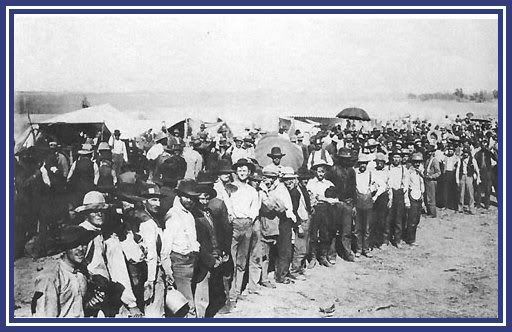

Opening of the Cherokee Strip

Cherokee Strip Land Run in 1893

The Shooting of James R. Hill

September 16, 1893, marks one of the biggest events in Oklahoma history, the opening of the Cherokee Strip. It also marks the first of many tragedies of the run, the shooting of James R. Hill.

Mr. Hill was a wealthy and highly respected man from Keanston, New Jersey. He was a chemist and for years held that position with the Standard Oil Company. He left New Jersey in August of 1893 to make a visit to the World Fair in Chicago, taking with him a nephew, Joseph R. Hanley of Altoona, Pennsylvania. He stayed in Chicago only one week and hearing of the opening of the Cherokee strip, he became determined to try his luck at getting a farm in the territory. On September 4, 1893, he left for Arkansas City to make his preparations. He wrote a number of cheerful letters to his wife, telling her that he was fairly certain of securing a homestead. He wrote her not to join him until after the rush was over, but she had all her preparations for the journey made and only waiting a telegram to start,when instead she received the news of his tragic death.

On the day of the run, Mr. Hill, along with his nephew, were along the Oklahoma border just south of Arkansas City. His plans were that he would make the run and stake a claim, while his nephew would follow behind with a wagon load of supplies. About 8 0' clock the morning of the run, permission was given for home seekers to go through on a road to the south side of Chilocco. Here Mr. Hill found a spot on the line on the southwest comer. The troops of the Third Cavalry ordered all runners to keep directly south and not to go southwest, as they had three miles start of those on the state line west of the school. They also said that they had orders to shoot anyone disobeying the order.

Nearing 12 o'clock noon, someone in the crowd fired a revolver. Thinking it was the signal to start, Mr. Hill, along with the rest of the southwest comer, broke loose from the soldiers ahead of time. One soldier, Asa Sousan, shouted for Mr. Hill to halt, but Mr. Hill did not heed him. The soldier took after him, taking aim he fired two shots, one hitting Mr. Hill in the back of the head.

The body was taken to Arkansas City where the citizens became outraged. A mass meeting was held and resolutions were adopted, demanding the surrender to civilian authorities the soldier who killed the unfortunate man, with Lieutenant Caldwell of the Third Calvary refusing the request. He stated that he made a full investigation and reported the killing of Mr. Hill by the soldier to his commanding officer and the full extent of his crime. He said the soldier had no intention of killing Mr. Hill, that he only intended to kill the horse, but being a poor marksman he killed the rider.

The story reached Delegate Flynn of Oklahoma who ordered a full investigation. Col. Edward M. Heyl, of the U.S. Army arrived in Arkansas city. At Behard Store in the city, he took all the facts and names of witnesses in regard to the killing and reported back to Washington. One of these witnesses, Will Fishback, told the best eye-witness account of the shooting.

Mr. Fishback very narrowly escaped being shot by soldiers on the day of the race. He was close to Mr. James R. Hill when the false alarm sounded and Hill held back a little but, thinking it was a go followed Hill. He saw the soldier shooting at Hill and saw him take deliberate aim and kill him. The soldier then turned and fired several shots at him, which whistled all around and close to him. Will had presence of mind enough to pull his horse aside and ride into a canyon where he was protected from the bullets. The soldier then fired at the next man and shot off his nose. There were several witnesses to each of these events, and it is not strange that people held an indignation meeting.

Was the shooting necessary and how about the line in Hunnewell, Kansas to the west? Well they had the same problem, but handled it a little better. It lacked nearly three minutes of noon when far off in the east a report of a shot was faintly heard and the line began to waver and horseman darted out in front. The officers started to order them back, but seeing the uselessness of trying to stop the human avalanche wisely desisted and contented himself with pulling his pistol and firing the official signal to "Let 'er go" and they went.

Necessary or not, one man laid dead. Lieutenant Caldwell and the Third Calvary were soon ordered to return to there post at Fort Riley, where Asa Sousan received his just punishment. The body of Mr. Hill was taken back to New Jersey by his nephew, and laid to rest. The people of his little village were horrified at the news of his tragic death. A life is a very big price to pay for a chance at free land in the Oklahoma Territory.

The Registration Booths

To comply with the proclamation of the U.S. Government on the opening of the Cherokee Strip, a registration was required at booths along the border, at Kiowa, Hennessy, Orlando, Stillwater, Caldwell and Arkansas City. At these locations settlers had to face many kinds of hardships.

The booths business was greatest outrage the people had to put up with. There was a rumble of discontent along the line because of the force at the booths were not large enough to register at all. There were fully 8,000 people in line daily, only between 2,700 to 2,900 were able to register daily. Many men and women spent two nights and two days in line. When registration stopped in the evening the lines were much longer than the morning hours. The tall enders, many of them received their numbers and came to the nearest city to spend the night. Those in the front ranks spent the night in line, sleeping upon the ground.

The Arkansas City Traveler said this about the settlers of '93: "To appreciate the courage these home seekers re displaying one must visit the booth and see what they are undergoing in order to secure a chance for a home. To note under what difficulties these men are laboring. Sleeping upon the ground along side of the highway covered with 6 inches of dust and drinking water that under ordinary circumstances you would refuse to give to your cow or horse.

Among the thousands in line at the booth was a man without legs, both limbs being off close up to his body. When seen by a reporter he was in line a quarter of a mile back from the booth. Although obliged to sit on the ground where he would get the full benefit of the clouds of dust that literally rolled over him, he was one of the jolliest men in the crowd."

Another suffering the settlers had to face on the line was the heat. The dust and heat was terrible and caused great inconvenience to the boomers. Sunstrokes were reported daily and death was not uncommon. On September 14, at the registration booth at Hunnewell, Kansas, thirty-two sunstrokes were reported along with two deaths.

Some settlers soon found and easier way to obtain their registration. G. W. Vaughn related how he bribed the soldiers at the booth in order to get registration without delay. He was approached by a man when he was at the rear of the line and told that he could get himself registered for $1.50. He went with the man and gave him a $1. He was told that when he saw a soldier raise a stick to go to the booth and give him a half dollar. He did so and passed inside. In the tent he met another soldier who told him to get out. He slipped another half and was registered. Mr. Vanghn wasn't the only one, for many settlers had this same story to tell.

Arkansas City, on the last day of rest, rations helped in stopping the anxiety and suffering. The booth was moved to the city and set up in the A.A. Newman's vacant store room. At an early hour the booth opened and was greeted with two long lines. At 7 o'clock the registration commenced and the people were registered at a lively rate. Twenty-five clerks were at work and as high as 20 per minute were registered. How any the suffering could have been avoided if the booths had been located in the cities along the border than on the wide open plains.

Looking at these settlers along the border we see a lot of strong will-power. I guess the difficulties they face at these registration booths was just one more price they had to pay for a chance at "Free Land" in the Oklahoma Territory.

Sooners, Prairie Fires, and U.S. Marshals

When the shots were fired on the line, the rush was on. Boomers dashed across the prairies with their claim flag in hand. Land for the taking, free land, but little did they know what was before them. Sooners, Prairie Fires, and U. S. Marshals.

Prairie fires ran wild and many casualties were reported daily from the strip. The most horrible perhaps was the death of Mrs. Elizabeth Osborn of Saginaw, Missouri. At age 76, she and her husband had made the run for a claim on Duck Creek bottoms, when a prairie fire came sweeping along behind them. Some man collided with their wagon and it broke down in the race. When seeing the fire coming, Mr. Osborn cut his horses loose and started to run for Duck creek. Mrs. Osborn started to run too, but was caught up in the fire and burned to death. After the fire had swept over the husband and several men, they took the body, wrapped it in blankets and buried it in a grave on the banks of Duck Creek.

U.S. Marshals were soon called in to look over these boomers. Protection from lawlessness and daily check of camp fires were needed. Not all marshals were honest and respectable men, as H.L. Hembec found out. While he and two parties were in there tents on a claim, three drunken U'S. Marshals came along and arrested the whole party for horse stealing. They were handcuffed and hained and taken to Blackwell, where they were turned over to the sheriff. After remaining there for some time, and being subjected to many indignities, they were taken to Kildare to await the Santa Fe train. Here they were made to sleep on the ground in handcuffs and chains and were otherwise badly treated. During all this time they protested their innocence, but it was in vain. Mr. Hembec was soon approached by a lawyer at which time he told him he was an honest man and a respected citizen of Ashton, Kansas, and that his mends there could prove his innocence. The lawyer told him that he would have him released in five minutes if he would pay him $10 dollars. Mr. Hembec readily agreed to this, but not having the money with him, S.B. Snider, who lived northeast of Gueda Spring, was called in to get his bond. The other parties did the same. Later it was discovered by Mr. Hembec that the lawyer and the u.S. Marshals were dividing the money made by these poor boomers, for their own personal use.

Sooners were everywhere after the run. Men who crossed into the Strip a long time before the opening date, jumped from there hiding places ready to claim their land. One sooner, Asa Youmans, who formally lived in Carthage, Missouri, had come to the Strip in a company of Missourians, who were regularly organized and paid by syndicate of real estate men, tried to face off the boomers from the line. When the first runners reached the Chickaskia River, near Blackwell, they found fifty men holding down claims with no other baggage then their rifle. Youmans was holding two, claiming that his mends and partners had gone on a search of water. The first-comers did not attempt to dislodge him but those who came later, planted their flags, determined to stand by them. Youmans came up to two of them and ordered them of with his rifle. One of the men asked him for his certificate. He said he had none an did not propose to get one, that he had support enough to make a good his claim, adding: "I am a sooner and I'd like to know what you are going to do about it?" The two men, covered as they were by his gun, went away, but less than an hour returned with at least two dozen friends, captured Youmans and proceeded to make him ready for trial by Judge Lynch. In what was probably a spirit of bravado, Youmans said he killed two settlers and would get away with some more. This upset the men so much that they pulled him up to a tree where they left his body as warning to others.

The story of Asa Youmans has always interested me, for on that day in '93, my great-grandfather, James Thomas Whitehead, made the run from Hunnewell, Kansas and staked his claim on the banks of the Chickaskia River, three miles north of Blackwell. Could he have been one of these men who faced Youmans? Maybe. But one thing we do know that Sooners, Prairie Fires and crooked u.S. Marshals were just three more thing these brave boomers had to face on the great race of 93.

|